The collapse of the biodiversity

Human activities are the origin of a massive decline of the biodiversity and ecosystems

Over the last 500 million years, the Earth has undergone five major events in which life almost disappeared completely. These upheavals were caused by massive geological and climatic changes, such as periods of glaciation, massive volcanic eruptions or the impact of a meteorite 65 million years ago, which wiped out entire species such as the dinosaurs. These events are known as ‘mass extinctions’.

Today, it seems that we are in the midst of a sixth mass extinction, this time mainly due to human activity. This extinction is affecting not only terrestrial, but also marine and freshwater ecosystems.

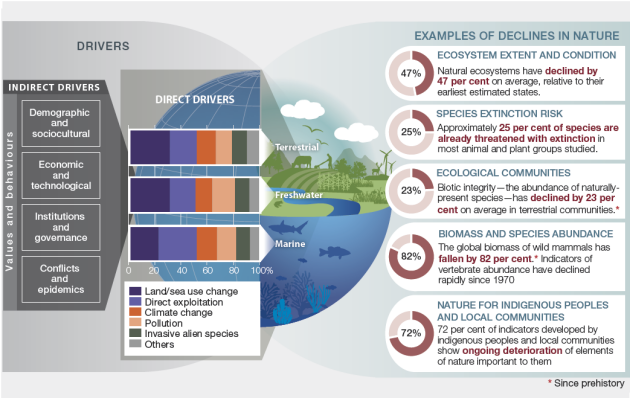

The main causes of this decline are

Changes in land and sea use (mainly driven by agriculture, deforestation and urbanisation)

Direct exploitation of species (hunting, fishing, etc.)

Climate change

pollution

Introduction of foreign species that disrupt local ecosystems

These causes are linked to structural factors such as demographic growth, our consumption patterns, the global economy, our techno-industrial systems, geopolitical decisions and armed conflicts. On a global scale, land use change is the factor having the greatest impact on terrestrial and freshwater ecosystems. In marine systems, fishing has had the greatest impact on biodiversity over the last 50 years, affecting both target and non-target species and their habitats. Although climate change, pollution and invasive species are having less of an impact at the moment, these effects are rapidly increasing.

To measure the extent of the damage, several indicators are revealing:

Natural ecosystems have shrunk by an average of 47% compared with their initial state.

The global rate of species extinction is now tens, if not hundreds, of times higher than the average over the last 10 million years, and this rate is accelerating. Around 25% of species in many animal and plant groups are already threatened with extinction.

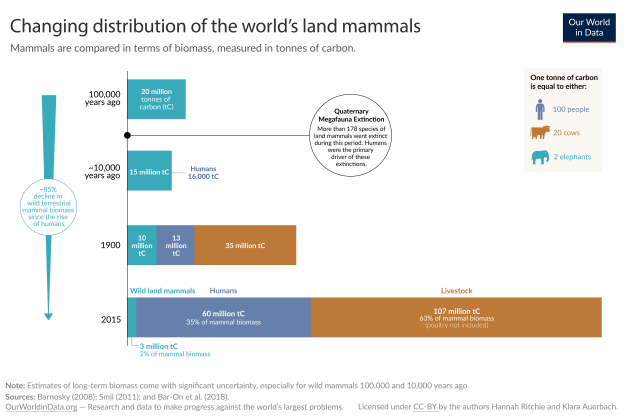

The global biomass of wild mammals has fallen by 82%. Since 1970, vertebrate populations in general have been declining rapidly.

The ecosystem services are essential for humanity's survival

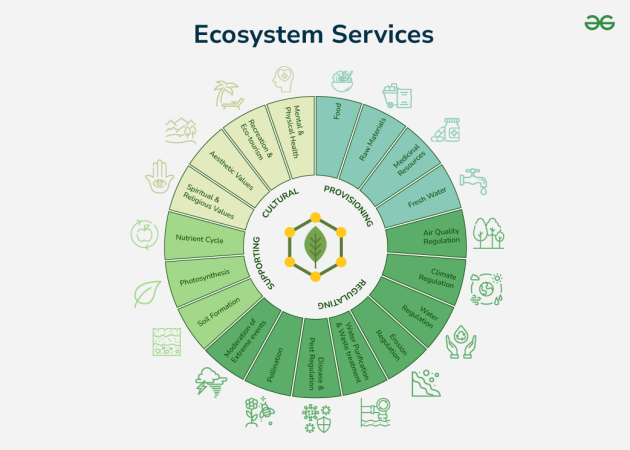

Nature makes a vital contribution to the survival, health and well-being of human populations. These essential contributions to our quality of life are known as ecosystem services. These services can be divided into three broad categories:

Regulatory and support services: these are the services that help maintain the balance of living conditions on Earth, such as air and water purification, climate regulation and photosynthesis.

Material contributions: these are the physical resources we obtain from nature, such as drinking water, food, wood and medicines.

Non-material contributions: these are the intangible benefits that nature provides, such as beautiful landscapes, tranquillity or spiritual inspiration.

It is important to understand that most of the services provided by nature are not entirely replaceable, and some are irreplaceable. Some may have man-made substitutes, but these alternatives are often imperfect and very costly. For example, to obtain drinking water, we can either use natural ecosystems such as wetlands that filter out pollutants, or resort to water treatment plants. However, these human infrastructures are much more expensive to build and maintain, and they do not offer the additional benefits that nature could provide, such as creating habitats for other living things or recreational areas for humans. Similarly, to limit coastal flooding, we can either protect the coasts with mangroves or build dykes and breakwaters. While human infrastructure can be effective, it does not offer the additional ecological and social benefits that natural ecosystems do.

The loss of biodiversity and the deterioration of the ecosyste services threaten the human health

Nature makes many essential contributions to human populations. Their decline is a threat to our collective health and well-being. Biodiversity and ecosystems contribute to (among other things)

The supply of a wide variety of foods, medicines and drinking water.

Help to regulate disease and ensure that the immune system functions properly.

Reducing air pollution by lowering levels of certain pollutants.

Improving mental and physical health through access to natural areas, among other benefits.

Their endangerment and the resulting disruption of benefits have direct and indirect consequences for public health and can amplify existing inequalities in access to medical care or healthy food.

In its 2019 report on the Global Assessment of Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, IPBES assessed global trends in nature's capacity to maintain its contributions to a good quality of life. The conclusions showed a decline in 14 of the 18 categories from 9170 to the present day (see Figure below).

Two tangible examples : the emergence of zoonoses and food insecurity

The emergence of zoonoses is encouraged by the decline in biodiversity caused by human activities.

The Covid-19 pandemic illustrated the major risk that the emergence of a zoonosis can pose to public health and the smooth running of our societies.

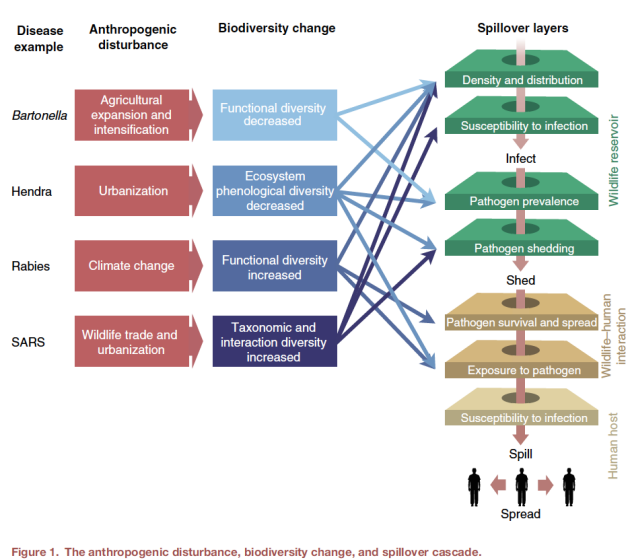

Today, the scientific researches shows the deep impacts on the biodiversity caused by human activites can increase the risk of transmission of animal diseases to humans (called 'spillober zoonotique') Several key points stand out from those researches :

Destruction of natural habitats: When habitats are destroyed, animals, insects and humans live closer together, making it easier for diseases to be transmitted between them.

The disappearance of large predators and animals: The loss of large animals that regulate ecosystems (such as certain predators) can lead to a proliferation of small animals, such as rodents, which are often reservoirs of disease.

Landscapes modified by man: By modifying environments (for example, through agriculture or urbanisation), we favour certain species that adapt well to these changes. This increases the chances of disease-carrying animals encountering humans.

Disturbance linked to human activities: The trade in domestic and wild animals, as well as agriculture, introduces foreign species that were not previously present. This multiplies interactions between different species, creating more opportunities for diseases to be transmitted from one animal to another, and sometimes to humans.

In short, the various changes caused by man, when combined, can increase the risk of transmission of new diseases from animals, as they disrupt the natural balance and favour situations conducive to the emergence of new pathogens.

To understand mechanisms connecting anthropogenic disturbance with spillover via biodiversity change, it is imperative to investigate how anthropogenic disturbance impacts biodiversity, and how those effects drive the perforation of the layers (intermediate processes) leading to spillover. Zoonotic spillover arises from the alignment of multiple processes (depicted as layers). Apart from human susceptibility to infection, we found that each layer can be affected by biodiversity change, especially when considering biodiversity along multiple axes. Connectingbiodiversity change to explicit processes helps us to better understand how, when, and why biodiversity change impacts zoonotic disease risk.

Food insecurity and malnutrition are exacerbated by the decline in pollinating insects..

Insect pollination supports agricultural production of many healthy foods that provide essential nutrients and help prevent non-communicable diseases. Some 70-75% of crops depend on insect pollination, which accounts for 35% of global agricultural production, according to the IPBES. This includes crops such as fruit trees, berries, vegetables, oilseeds (such as rapeseed) and pulses (such as peas and lentils).

Today, most crops receive insufficient pollination due to the low abundance and diversity of pollinating insects. Pollinating insects are in decline as a result of the impact of human activities on ecosystems: changes in land use, intensive farming techniques, harmful pesticides, nutritional stress and climate change. The number of pollinating insect species and the population sizes of many species are declining at an alarming rate. In some parts of the world, this decline is reaching levels of 70-90%. According to a 2016 IPBES report, 9% of bee and butterfly species are threatened in Europe, and populations are declining for 37% of bees and 31% of butterflies.

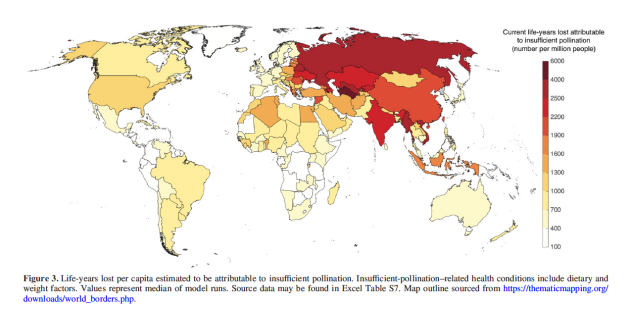

A study published in 2022 by a team from the Harvard TH Chan Shcool of Public Health's Department of Environmental Health modelled the impacts of insufficient pollination on current global health, focusing on food. The study estimated that, on a global scale, 3 to 5% of fruit, vegetable and nut production is lost due to insufficient pollination, resulting in an estimated 427,000 additional deaths each year due to the loss of healthy food consumption and related illnesses. The impacts were unevenly distributed: the loss of food production was concentrated in low-income countries, while the effects on food consumption and mortality were greater in middle- and high-income countries, where non-communicable diseases are more common.

The consequences of this decline for human health are therefore considerable and are likely to worsen, in a world where almost 821 million people are already suffering from food insecurity, and where around 2 billion others are facing micronutrient deficiencies.