Health and environment global context

Today, global health is more and more weakened by the deterioration of our environment. To illustrate this point, we can cite Dr Jean-David Zeitoun, epidemiologist, that says in his book "Le suicide de l'espèce" :

"What is the futur of global health? The answer is clearely: we don't know."

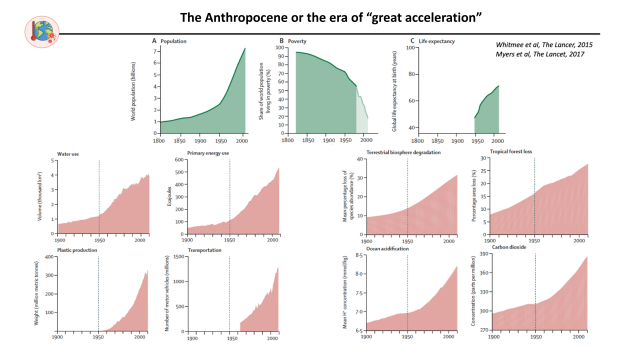

The Anthropocene or the era of ‘great acceleration'.

Today, we live in the Anthropocene era, a new geological era in which the human race, through its activites, has become the dominant geological force. This period, characterized by the deep imprint of the Human on the biosphere, succeeds to the Holocene (an interglacial period lasting more than 10,000 years, during which stable and favourable climatic conditions allowed human societies to expand). Although the issue is still debated among scientists, it is generally considered that the Anthropocene began with the Industrial Revolution of the 19th century, marked by an intensification of human activities.

From the 1950s onwards, we entered the ‘Great Acceleration’, in which human activities altered ecosystems more rapidly and more profoundly than in any other comparable period in human history. In just a few decades, the consumption of resources such as fresh water, energy and materials (metal, paper, plastic) increased almost exponentially. This sharp rise necessarily translates into an impact on the environment on the same scale, such as the loss of biodiversity, the increase in carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, the acidification of the oceans and tropical deforestation. Paradoxically, these trends have been accompanied by constant improvements in life expectancy. Many of the same scientific and technological advances that have amplified our impact on the Earth's natural systems have also increased our access to abundant and inexpensive energy, improved per capita food production despite the rapid growth in the world's population, and reduced poverty on a global scale.

Human health: historic progress over the last two centuries ...

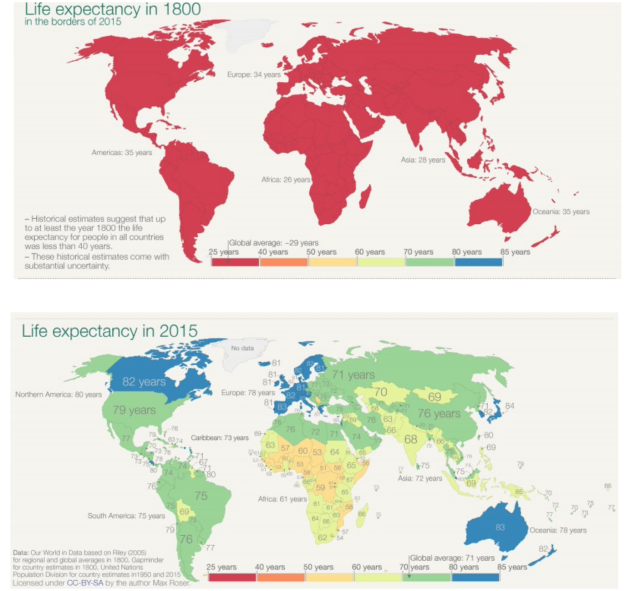

Historically, life expectancy has risen from 29 years in 1800 to 71 years in 2015, with improvements in most human health indicators.

However, as we shall see below, this progress is no longer a given. Whereas until now, the state of human health and that of our planet's natural systems have followed opposite trajectories, it would appear that we have mortgaged the health of future generations in order to build the world in which we live.

Human health: ... now at risk!

Several indicators suggest that we are at a breaking point, where advances in human health are no longer invariably set to progress.

These include

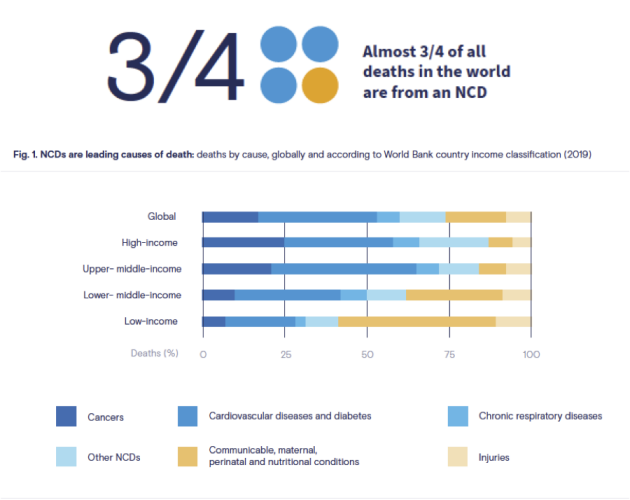

The epidemic of chronic non-communicable diseases. The four main non-communicable diseases (NCDs) - cardiovascular pathologies, cancer, diabetes and chronic respiratory diseases - as well as mental disorders, account for a significant proportion of deaths and health problems. Each year, 74% of global mortality is attributable to these causes.

The deterioration in children's health, as shown by the increase in the incidence of paediatric asthma, type 2 diabetes in children and adolescents, and the worrying deterioration in the mental health of 11-24 year-olds.

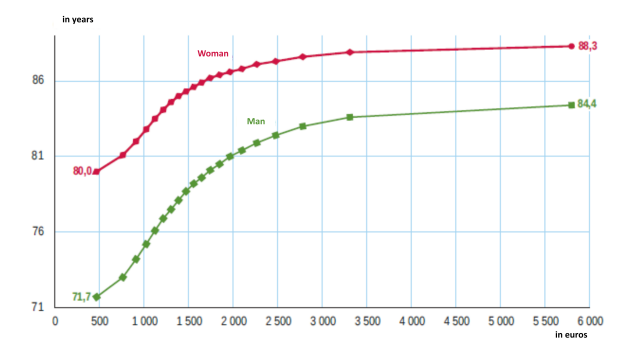

Persistent social inequalities in health. In France, there is a 13-year gap in life expectancy between the wealthiest 5% of men and the poorest 5%.

Note : en abscisse, chaque point correspond à la moyenne des niveaux de vie mensuels d'un vingtile. Chaque vingtile comprend 5 % de la population.

Lecture : en 2012-2016, parmi les 5 % les plus aisés, dont le niveau de vie moyen est de 5 800 euros par mois, l'espérance de vie à la naissance des hommes est de 84,4 ans.

Champ : France hors Mayotte.

Our health is planetary : how environmental degradation threatens public health

To understand the reasons for this shift, we need to look at what environmental epidemiologist Professor Rémi Slama said in his inaugural lecture at the Collège de France in 2022, where he held the annual chair in Public Health: ‘Much has been researched and taught about disease as an internal and curable phenomenon; I would like to emphasise here the complementary vision of disease as an external and preventable phenomenon’. In other words, our health is largely modulated by environmental and social health determinants.

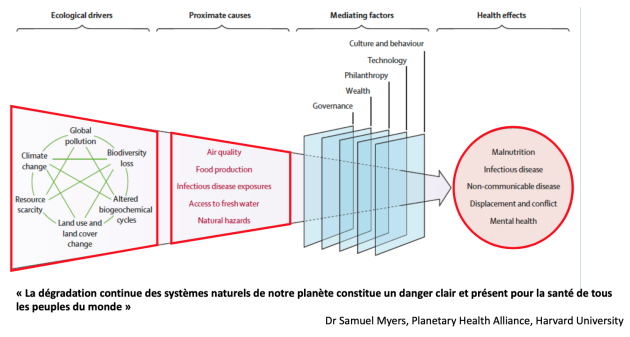

Human activities are causing profound upheavals in natural processes, undermining the stability of our planet's vital systems. These biophysical changes manifest themselves in at least six dimensions: (1) disruption of the global climate system; (2) widespread pollution of air, water and soil; (3) rapid loss of biodiversity; (4) reconfiguration of biogeochemical cycles, particularly of carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus; (5) changes in land use and cover; (6) scarcity of resources, particularly fresh water and arable land.

These environmental changes have a direct impact on the determinants of our health: they affect the quality of the air we breathe, the water we drink and the food we produce, as well as our exposure to infectious diseases and natural disasters (heatwaves, droughts, floods, etc.).

These disruptions then have a negative impact on all aspects of our health: nutrition, infectious diseases, non-communicable diseases, displacement, conflict and even mental health.

This ecological and health crisis is rooted in and reinforces deep-rooted ecological and social injustices, already disproportionately affecting vulnerable groups who have contributed least to the crisis, such as the populations of the Global South, indigenous peoples and racialised people.

In this context, planetary health is a global and transdisciplinary approach that aims to shed light on the complex links between environment and health, with a view to identifying sustainable solutions for building a healthy, habitable and socially just world in the face of the systemic challenges facing humanity.

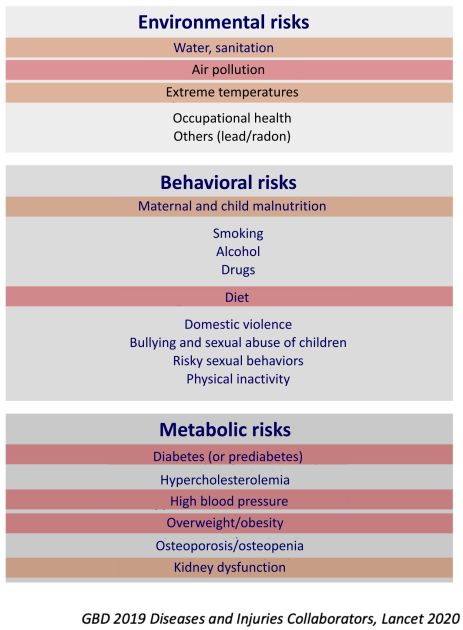

Another way of approaching the problem is to look at it from the angle of health risks. As shown in the figure below, these can be classified as environmental, behavioural and metabolic risks. Most of these risks are exacerbated by the current socio-economic organisation of our societies, our dependence on fossil fuels and our Western lifestyles. Jean David Zeitoun sums it up on the back cover of his book Le Suicide de l'Espèce: ‘Global society is producing more and more diseases, while spending ever more to try to treat them. The short answer to this contradiction is that the environmental, behavioural and metabolic risks that cause disease are consequences of economic growth’.

Understanding these interactions is therefore crucial to improving public health.

The remainder of this first chapter will be devoted to exploring four dimensions of the inextricable links between health and the environment: climate change, air pollution, the collapse of biodiversity and food.