Co-benefits of sustainable mobility

Environmental and health impacts of motorised mobility

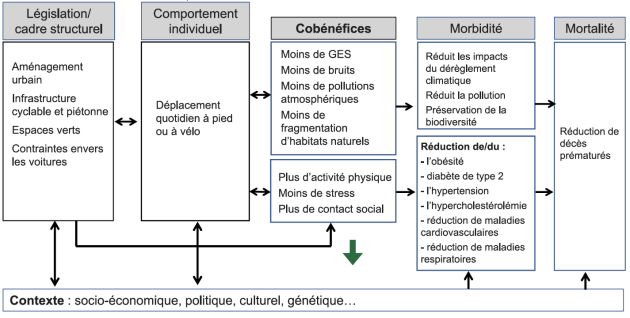

Mobility is a major source of greenhouse gas emissions worldwide. In Europe, the transport sector is the second largest contributor to GHG emissions, and the largest in France, where it accounts for 31% of national emissions. Of these, around 50% are due to cars. Before vehicles are used, their production and the construction of road infrastructure require the extraction of non-renewable resources, fragment natural areas and also contribute to the emission of atmospheric pollutants and greenhouse gases.

At the same time, motorised mobility has a major impact on health, particularly as a result of :

Air pollution: In cities, intensive use of motorised transport is responsible for 70% of urban air pollution. In 2010, road transport accounted for 40% of the economic costs associated with premature deaths due to air pollution in the WHO European Region.

A sedentary population: A lack of physical activity is responsible for a considerable overall burden on health, with around 7% of deaths from all causes attributable to this cause. This burden is even greater in Europe, where around 10% of deaths and 30% of direct healthcare costs for non-communicable diseases (type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, respiratory diseases, cancers) and mental health disorders are due to physical inactivity. In Western countries, over 40% of the population is insufficiently physically active, with no downward trend over time. The WHO estimates that physical inactivity causes around one million deaths each year in Europe.

Noise: Noise pollution from transport is associated with cardiovascular disease and has deleterious effects on children's sleep, stress and cognitive development.

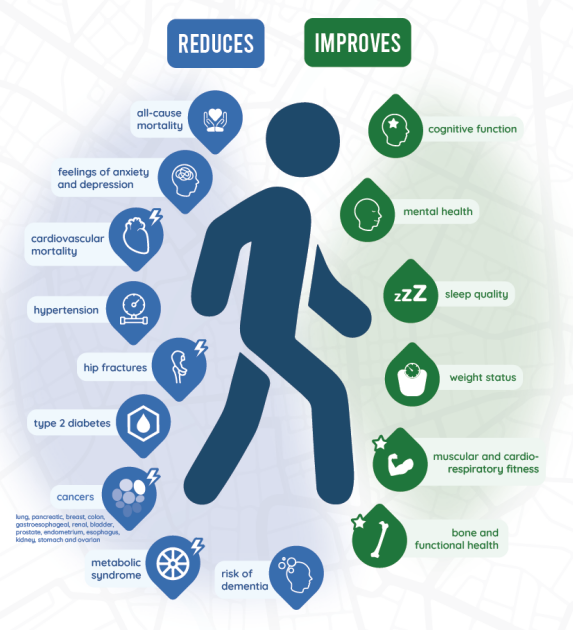

Promoting active mobility: positive impacts on individual health

Physical activity is an essential determinant of health. A wide range of epidemiological studies have associated moderate-intensity physical activity with a reduced risk of all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, several types of cancer, type 2 diabetes, dementia and depression. The greatest benefits are seen in inactive or low-activity individuals who manage to incorporate a little activity into their daily routine. People who reach the minimum level recommended by the WHO, i.e. 150 minutes of moderate physical activity per week, enjoy at least 70% of the potential benefits. It is precisely these characteristics (moderate intensity, regularity of practice, benefits appearing even at low levels of activity) that make active modes of transport, such as walking and cycling, perfect sources of physical activity. Numerous studies have shown that active travel leads to higher overall levels of physical activity.

With regard to the concern that pedestrians and cyclists may be exposed to air pollution during their journeys, health impact assessments show that the benefits of physical activity outweigh the harmful effects of air pollution, even for very high levels of air pollution. Furthermore, a shift from motorised urban transport to walking and cycling could reduce air pollution emissions and lead to a reduction in health risks for urban populations. Beyond the issue of modal shift towards active mobility, a structural transformation of energy production systems away from fossil fuels (by reducing our consumption and using ‘clean’ energy sources) would have substantial health benefits through improved air quality. For example, improvements in air quality would help prevent the 1.2 million deaths a year caused by exposure to PM2.5 from fossil fuels.

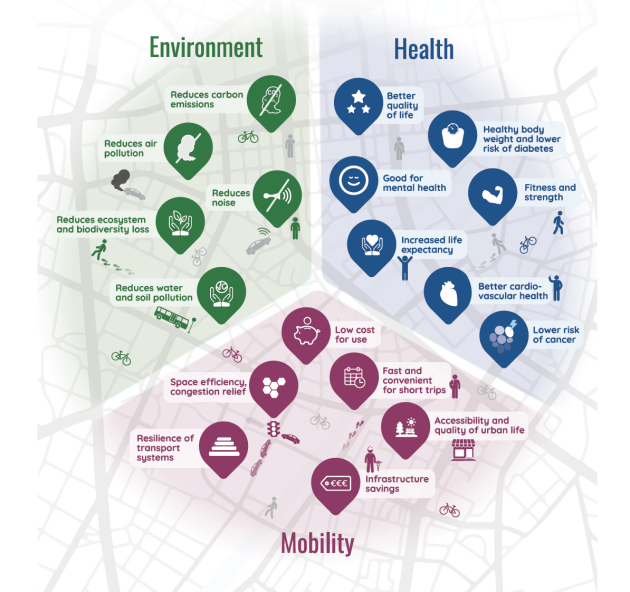

Promoting active mobility: environmental and community benefits

Switching from car-based transport to walking and cycling offers an opportunity to optimise urban planning. Walking and cycling are space-efficient modes of transport - an increasingly crucial aspect as the urban population continues to grow and transport competes for more and more limited space. In urban centres where space is at a premium, encouraging space-efficient modes of transport would make it possible to develop green spaces and meeting places, bringing benefits in terms of physical and psychological well-being for the population, while facilitating better regulation of temperature and rainwater.

Unlike electric cars, which are still largely powered by energy from fossil fuels, active modes of transport are essentially carbon neutral and play a key role in reducing emissions. When comparing carbon dioxide emissions throughout the life cycle of each mode of transport, taking into account emissions related to the manufacture, energy supply and disposal of the vehicle, empirical research suggests that emissions per kilometre are at least 30 times lower for cycling than for a car powered by fossil fuels, and around ten times lower than for an electric car. Promoting active mobility could therefore play a substantial role in helping to achieve ambitious greenhouse gas reduction targets through appropriate public policies and investment in suitable infrastructure.

Overall, active mobility costs public authorities considerably less than other modes of transport, as a number of national and international studies have shown.

A French study published in 2024 in the Lancet Planetary Health (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2024.100874), aimed to assess the impacts on mortality and morbidity associated with cycling in a country where cycling is relatively low, France, as well as the associated monetary benefits. The study also examined the potential additional benefits of switching a proportion of short journeys from car to bicycle, including projected savings in greenhouse gas emissions. The results of the study showed that the French adult population (aged 20-89) was cycling for an average of 1 minute and 17 seconds per day in 2019, with considerable heterogeneity according to gender and age. This prevented 1,919 premature deaths and 5,963 cases of chronic disease, with a significant proportion of these benefits accruing to men, who enjoyed almost 75% of the benefits. The direct medical costs avoided were estimated at €191 million per year, with an estimated average of €1.02 in intangible costs avoided for every kilometre cycled. If 25% of short car journeys (<5 km) were replaced by cycling, this would double the number of deaths avoided. This modal shift scenario would prevent €2.59 billion in intangible costs, while also generating significant reductions in CO2 emissions.